“Information, it is argued, cannot supply its own energy.”

-Shweder, 1992

Context

This is a brief overview of a model of moral cognition that I developed over some years. I’m walking away from research for awhile, and am sending out this summary like a message in a bottle. I’ve decided to call it the Is→Ought Model of moral cognition. A few citations are included below, but I’ve mostly set aside the academic convention of addressing data and alternate accounts. Hopefully, this stripped-down approach will make the thread of ideas easy to follow.

The basic claim of this model is that our sense of what we ought to do is built from our sense of what is the case (i.e., we derive “ought” from “is”). It is easy point out that is→ought inferences seem to happen in some cases, and a number of scholars have already done so. But I propose that “ought” derives from “is” entirely—in every case where “ought” is actually inferred and not merely parroted—and I sketch out a set of pathways whereby this translation from “is” to “ought” takes place within any mind or computational system that is capable of moral thought.

The part of the model that is most central and also most controversial, is where I draw a line between moral and nonmoral “oughts,” and list the ingredients needed to move from the nonmoral into the moral domain. There is a familiar and, I gather, tedious audacity in this attempt to distinguish the moral from the nonmoral, which rolls eyes and raises eyebrows. It’s been tried many times before. So, I need to offer a couple caveats:

First, this model is not at all about the content of moral judgments. That is, I do not ask whether particular actions are moral or immoral, or whether particular moral judgments are valid or not. Such questions are properly part of moral philosophy (for further elaboration of this distinction, read this article). Instead, I describe the form of moral thought, tracing the structure of an inference from nonmoral premises to moral conclusions.

Second, even this more constrained task of describing a universal set of pathways or structure of moral thought triggers reservations. Some point to Wittgenstein’s observation that words, including “morality” and “norm,” don’t have single meanings but instead can have many diverse meanings loosely connected through “family resemblance.” Let me just acknowledge, then, that my model may not cover every sense in which the word “moral” is used. Hopefully, the account below will make what I am trying to do clear enough.

The Is→Ought Model

I’ll start with an example. Suppose that you are assembling a chair using screws. How might you figure out which direction to turn a screw in this instance? What motivates you to act? In fact, you can figure out what to do with the screw by bringing together two pieces of information:

Belief #1: “Turning the screw clockwise tightens it.”

Belief #2: “My present task requires me to tighten the screw.”

Conclusion: “I ought to turn the screw clockwise.”

Here, two “is” premises lead to a conclusion about what you “ought” to do. “But hold on,” you say, “isn’t the conclusion just a restatement of Belief #1?” Not quite. Consider that it is possible to reverse the conclusion by changing Belief #2 (e.g., “My present task requires me to loosen the screw”). This fact suggests that Belief #2 is essential. Even if it is never put into words. Even if you never hear a voice in your head that says, “this task calls for some screw tightening,” an implicit knowledge of the task you are performing is still necessary because, without this information about the nature of the larger task (chair assembly), you would not know what to do with the screw. Finally, alongside this inference about which way to turn the screw, the motivation to actually go ahead and tighten it comes from your bigger-picture desire to assemble the chair, which is itself understood in a greater context of your activities and endeavors.

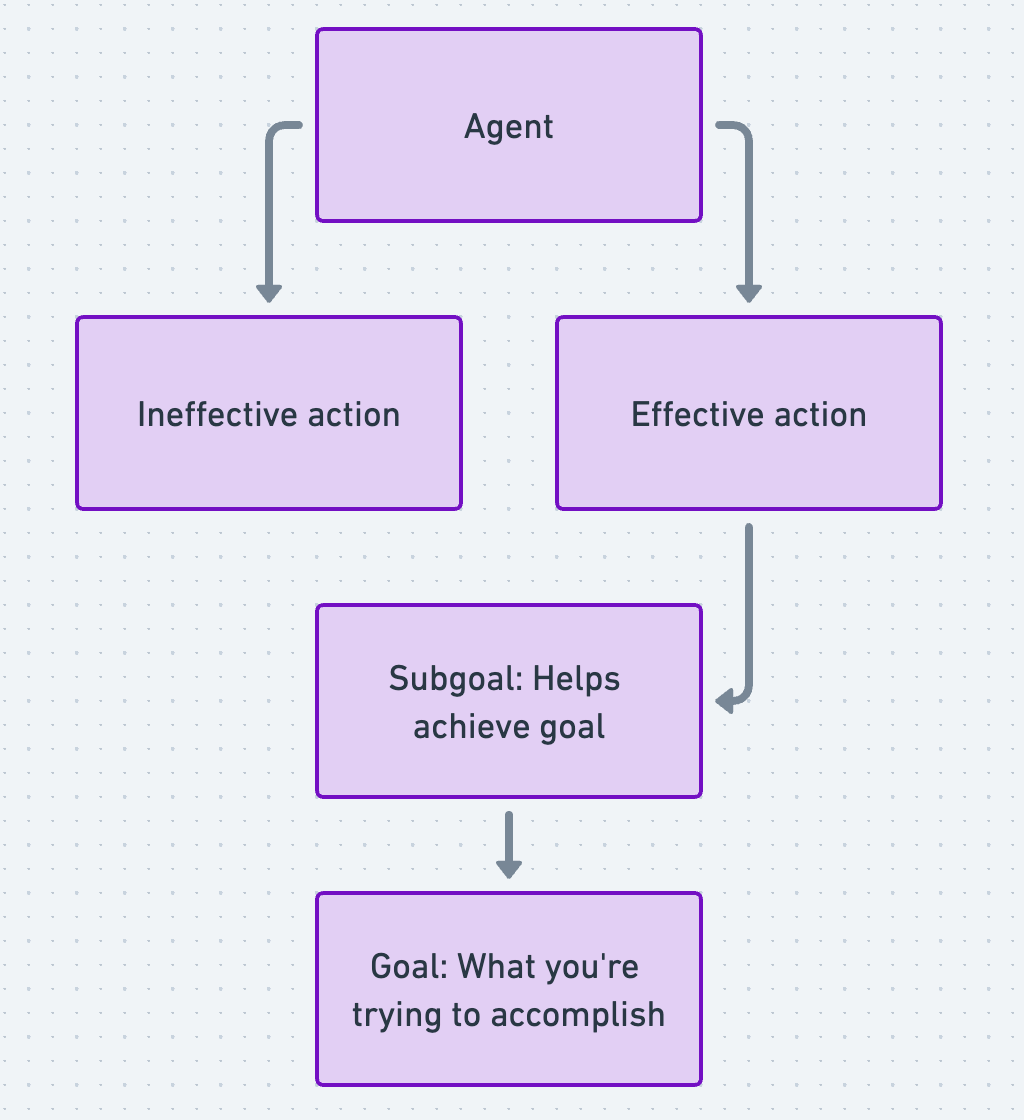

Image 1. How to derive “ought” from “is”: The general (nonmoral) case. Boxes contain beliefs about what “is” the case. Middle boxes—The status of an action as “effective” / “ineffective,” and of a task as a “subgoal”—are defined relative to the agent’s goal. In the context where the effective action serves the agent’s goal, the effective action is understood to be the correct action.

Now that we have seen that it is possible to infer “ought” from “is,” we may ask again—How? To answer this question, we have to investigate the process of understanding—i.e., the way in which we determine what “is” the case. The philosopher Martin Heidegger pointed out that our understanding of things is intimately bound up with our nature as beings with concerns and projects. For instance, one’s understanding that “this is a chair” carries within it a history of desires and needs, like the desire to rest comfortably or the need to sit and work on something. As a result of our personal involvement with things, there is latent value hidden within our mere understanding of what something “is”—value that is called forth by the right context. For instance, in the context where you want to sit down and rest, the value of a chair as a resting place becomes salient. In this moment, you do not see the chair merely in terms of its physical properties; instead, you understand the chair in terms of its value for sitting. And the value of the project of assembling a chair is also determined in advance by the value you attach to the chair you are assembling. This understanding of the value of the chair, and of your involvement in the project of chair assembly, is what motivates you to complete the smaller task of tightening the screw. When you realize that you should turn the screw clockwise, this “should” expresses the fact that you’d really like to put together this chair. There’s no need for any special transmutation from ontological “is” to normative “ought”—The “ought” is merely a translation of your preference for a chair over an Ikea box. In this case, “ought to turn it clockwise” expresses the direction in which you are headed—toward an assembled chair and away from a useless pile of chair parts.

This analysis echoes an insight of the anthropologist Richard Shweder, from whom I take my epigraph. Since the 1970s, Shweder had been observing people’s tendency to internally translate “is” statements into “ought” directives and to be motivated by all sorts of cultural content. To properly understand this translation from “is” to “ought,” Shweder proposed that we recover the ancient teleological view where “the idea of the ‘good’ is contained within the idea of reality.” This approach allows us to see how our definitions of many things express their value in a particular context.

By way of illustration, Shweder discussed the nature of a “weed.” “Weed” is not a value-free concept. It is instead an evaluation of a plant within a particular context. As a result, to merely call something a weed is to suggest something like, “this plant doesn’t belong here and should be removed.” Similarly, the mere recognition that a plant is a weed entails, in the context of a gardening endeavor, the conclusion that it ought to be pulled out. The content of this observation (this “is” a weed) is all you need to motivate the behavior (I “ought” to pull it). In Shweder’s pithy phrase, information supplies its own energy. (Note. This doesn’t mean that in every case you actually will follow through and pull the weeds. Nor am I suggesting that you are necessarily right to call a particular plant a weed.)

Now that we’ve seen how to translate from “is” to “ought” in the general case, whether drawing on Heidegger or Shweder for help, we are ready to consider the special case of morality. What’s the difference between a moral “ought” and a nonmoral “ought,” and what are the mental ingredients that distinguish the moral from the nonmoral? To illustrate my answer, let me expand upon the example of the screw:

Generally, if you decide you don’t want to assemble a chair, that’s your choice. You are under no obligation to screw in the screw. But we don’t always feel free to do what we want. Suppose you are an orthopedic surgeon, and the screw is going not into a chair but a patient’s hip. In these circumstances, you would probably not feel free to leave out the screw. Instead, layered atop the nonmoral “ought” specifying the right way to turn the screw would be another norm specifying that you ought to want to turn the screw and fix your patient’s hip. This higher-level “ought” is a moral norm. As with nonmoral norms, it emerges from a certain combination of nonmoral beliefs.

Image 2. This is a joke.

Here’s how it works. There are at least three mental pathways through which nonmoral beliefs create and influence moral judgments—I call them 1) ”building,” 2) “bending,” and 3) “attracting” pathways. Let us consider them in turn:

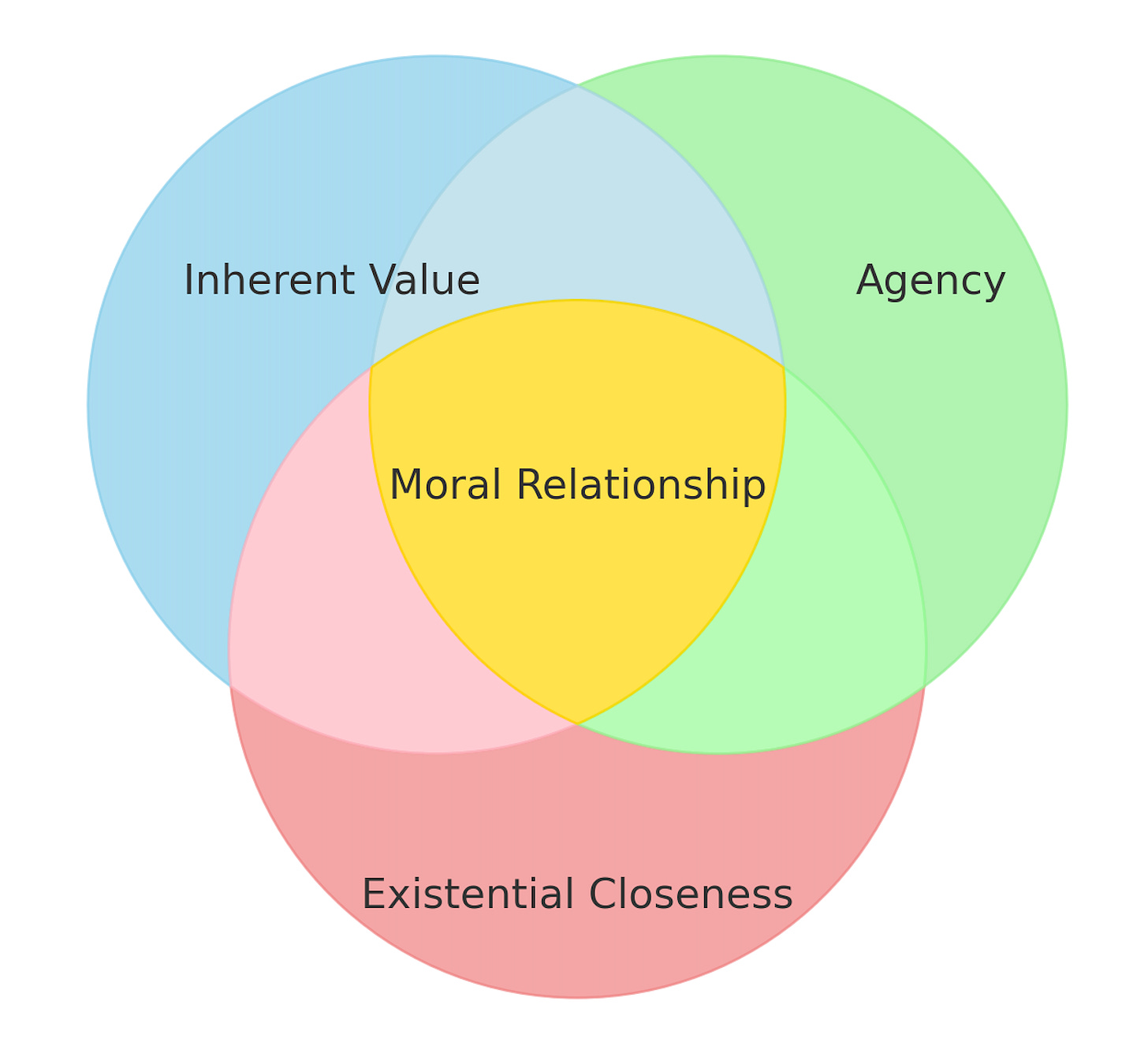

Builders

Most fundamental are the beliefs that build moral relationships. “Builder” beliefs include the belief that an object or “end” is inherently valuable, the belief that a subject has agency relative to the object, and the perception of existential closeness between subject and object. (Note: “Existential closeness” does not mean closeness in physical space. I’d be in a moral relationship with my daughter even if she was on the moon.) Moral relationships emerge when all three of these “builders” converge to define a relationship in one’s mind: e.g., “I have the capacity to behave better/worse toward _X_, who is worthy of my consideration and close enough that their wellbeing is my problem.” That’s the structure of a moral relationship—although the content will vary (I don’t agree, for instance, with the view that moral relationships are limited to relationships between people).

Image 3. Structure of a moral relationship.

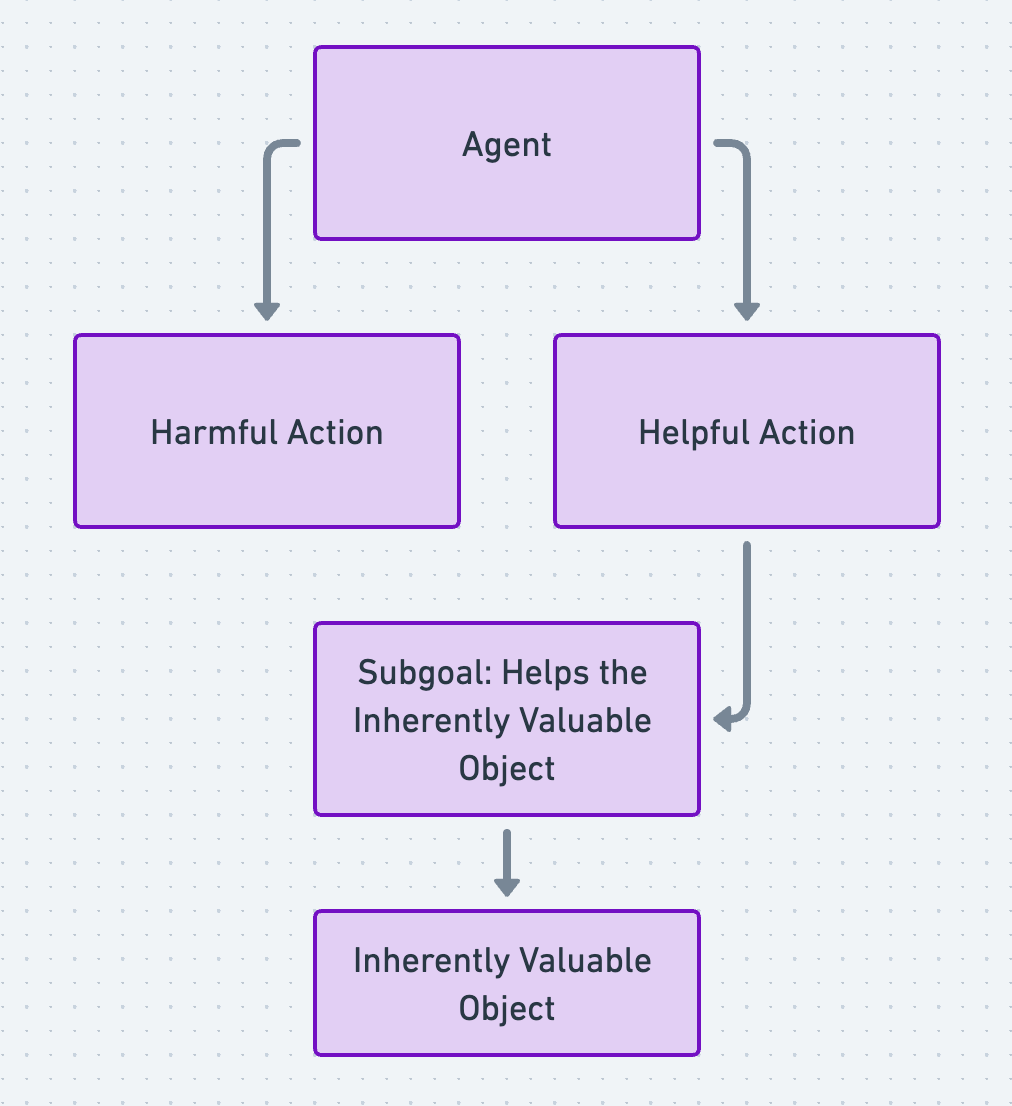

Moral relationships provide the motive force behind moral norms: i.e., The reason people feel motivated by moral norms is because, implicitly, they understand themselves to be in moral relationships. In the case of the screw, we saw that adding a moral relationship between doctor and patient also adds a moral dimension to the directive about how to turn the screw: Not only ought you to turn the screw clockwise because that is the effective way to screw it in (a nonmoral “ought”); additionally, you ought to effectively screw in the screw because that is what your patient needs (a moral “ought”). (Note: This felt sense of moral obligation is distinct from the legal obligations between doctors and patients, which apply even to doctors who feel no moral obligations at all toward their patients.)

Image 4. Inference from “is” to moral “ought.” Boxes contain beliefs about what is the case. Middle boxes—The status of an action as “helpful” / “harmful,” and of a task as a “subgoal”—are defined relative to the agent’s consideration of the object that they view as inherently valuable. The action that best serves the inherently valuable object is morally correct. (This simplified picture ignores the complexity that emerges from the fact that we are typically in numerous and shifting moral relationships, and may also feel some moral responsibility toward ourselves.)

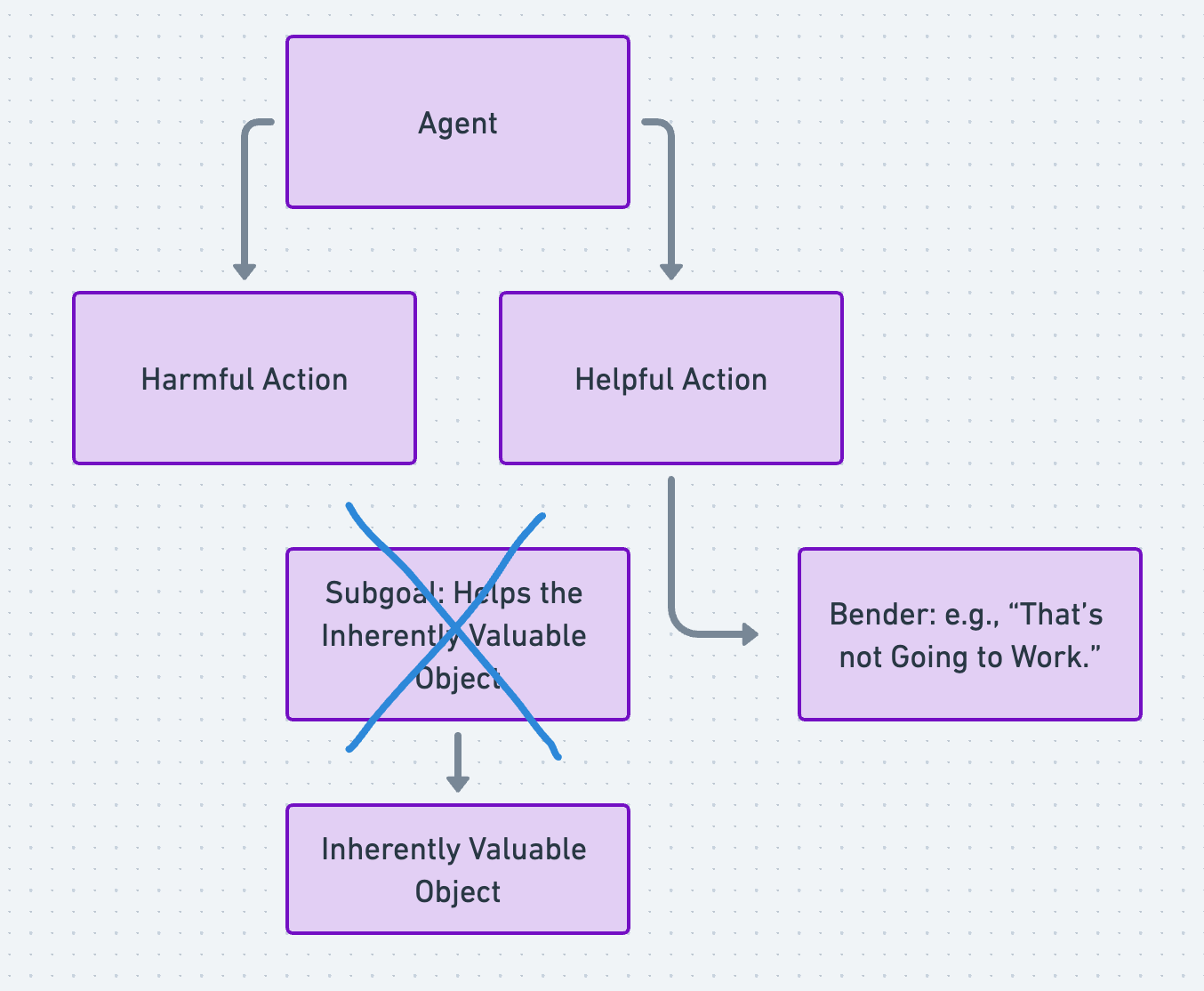

Benders

Once moral relationships take shape in a mind, other nonmoral beliefs become morally relevant. I call these secondary beliefs “benders” because they influence or bend chains of thought that already have moral content. For instance, if someone already feels a moral responsibility toward human life, then the question of when human life begins might influence their moral stance on abortion. If abortion is understood as a violation of one’s moral relationship with human life, this implies abortion is immoral; whereas, if abortion is understood as a woman’s decision in relation to her own body and future, this implies abortion is permissible. But when you examine the relevant beliefs in isolation, you can see that a claim like, “life begins as conception” is not a moral belief on its own. Rather, it’s a belief that has moral relevance only if you already assume a certain kind of moral relationship and a certain cultural context. It’s a bender.

Returning to our earlier example: Suppose you were standing over the patient and preparing to screw in his hip, when some staff member ran into the room and frantically stopped you: “You’re not a doctor! That man is not here for a hip replacement! And we don’t even use screws for hip replacements!” Any one of these statements, if accepted as true, would immediately negate your moral responsibility to screw in the man’s hip. Yet, none of them are moral statements, and they don’t negate your moral relationship with the man on the table. In this context, they are benders.

Image 5. A Bender influencing moral thought. Here, the bender redefines the helpful action as unhelpful.

Attractors

Finally, in addition to “builders” (beliefs that build moral relationships) and “benders” (beliefs that have secondary moral relevance in a certain context), there is an “attracting” pathway. Attraction refers to the ideological and social pull of beliefs or belief systems. For instance, even without really knowing why, a US Democrat may feel inclined to be pro-choice and a Republican may feel inclined to be pro-life. This reflexive attraction to a certain ideological perspective happens because we outsource cognition, to some extent, to others in our group. We don’t have to think so hard about where our conclusions come from, if we can verify that others have reached the same view. So, for example, the expression Democrat→Pro-Choice does not express a logical relation but a kind of attraction between one’s identity as a Democrat and one’s view on abortion.

Image 6. Are we better off thinking for ourselves?

Builders, benders, and attractors contribute differently to moral cognition. For instance, although the “attracting” pathway is pervasive, it is also relatively weak, since the premise of an attractor is not logically connected to the conclusion it supports. (Psychologist Joshua Rottman and I have demonstrated the weakness of attractors as compared to benders for predicting moral judgments, in an article that is languishing under peer review.) Bender beliefs are more robust than attractors, but they may still be quite weak. For instance, “benders” like “life begins at conception” are often generated to support a predetermined conclusion, and benders may also build upon premises that make no sense—just think of the justifying beliefs held by any religious group besides your own. By contrast, the most robust pathway into moral thought is the “building” pathway that originally creates moral relationships.

In the past, I have used the language of “perception” to describe moral relationships because I think that builder beliefs are so deeply ingrained as to be automatic and outside of our control, just like sensory perception. That is, it seems to me that we can’t help being in moral relationships and seeing things in moral terms. Instead, the trio of “perceptions” from which a moral relationship is built: 1) that something has inherent value (e.g., my daughter), 2) that I have agency (e.g., that I can choose to treat my daughter better or worse), and 3) that the inherently valuable object is “my problem” (e.g., that my daughter’s wellbeing is an issue for me) simply exist as an inevitable way in which my mind makes sense of the world.

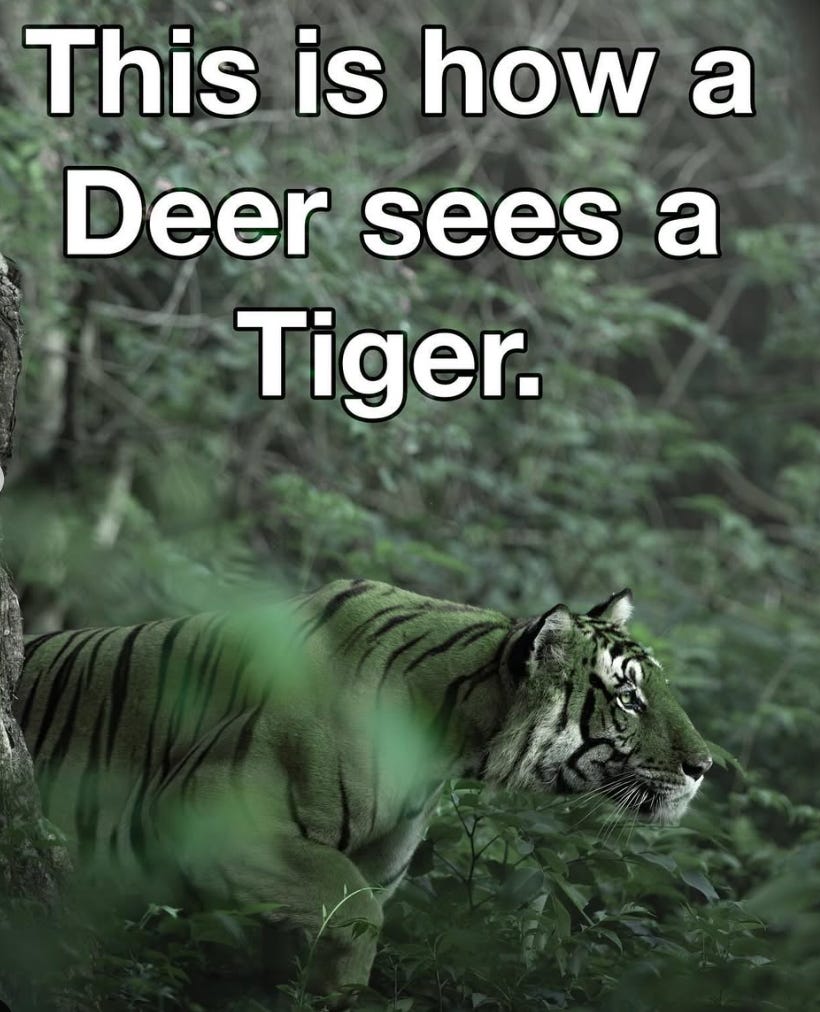

Image 7. What color is this tiger, really?

To be clear, I am not making any claim about whether inherent value really exists in the world, or whether people really have free will, or anything like that. Instead, I am expressing the view that these ways of seeing the world are (for most of us) inescapable—even if you engage in some high-level deconstruction of these beliefs and arrive at the conclusion that, e.g., nothing is inherently valuable and free will doesn’t exist. This is why I find the analogy to sensory perception to be useful. Consider that it is possible to deconstruct the idea of color and realize that no object in the world “possesses” any color, since color is a representation made up by one’s mind, and, in fact, different minds map different colors onto the same object, so that no color is objectively true. I can realize this fact about the contingent nature of color, but it won’t change the fact that the leaf on the houseplant in front of me looks green. In the same way, you might deconstruct your moral relationships and decide that nothing has inherent value, since value is a representation within your mind. And you may decide that no one really has any agency, whether the universe is causally deterministic or probabilistic. And yet, as long as you have the cognitive capacity of “moral sight,” these realizations will not stop you from feeling moral responsibilities toward your child.

Image 8. This is not how it happens.

These considerations reinforce the claim that the “builder” pathway is extremely robust. And yet, even this pathway is subject to our changing attention. We can mute our feeling of moral responsibilities for distant others by turning off the news or distracting ourselves, just as I can stop seeing my houseplant’s greenery by closing my eyes.

Conclusion

That’s the Is→Ought Model in its current form. It is an attempt to return moral psychology to the question that Shweder raised over three decades ago: i.e., How do descriptive beliefs (the “is”) give rise to normative beliefs (the “ought”), motivating us to behave in certain ways and not others? My proposal is that a set of three “builders” give rise to moral relationships. Then, once we are “in” moral relationships, other relevant “benders” influence how we reason about our moral relationships across various contexts. And, finally, our thinking is also influenced by the memetic and social pull of “attractors”—i.e., we are sensitive to zeitgeist and ideology and the opinions of in-groups. Together, these cognitive pathways conspire to determine our sense of how we ought to behave. Wherever and whenever we reach a strong conclusion that we “ought” to do one thing rather than another, there exists underneath this normative conclusion a set of “is” premises that are ultimately responsible for the conclusion.

Much work remains to be done if this “Is→Ought Model” is to become a robust theory that explains and predicts diverse moral beliefs and behaviors in arbitrary minds across arbitrary contexts. I really hope some young researchers take up the challenge. For now, however, I’m moving on to something new. I’ll be applying my research experience toward the area of business strategy consulting. If that seems like an odd left turn, that’s because it is. I could use advice, so please don’t hesitate to reach out to me and offer your two cents.

Citations

Beal, B., & Rottman, J. (In Press). Nonmoral beliefs are better predictors of moral judgments than moral values.

Beal, B. (2020). What are the irreducible basic elements of morality? A critique of the debate over monism and pluralism in moral psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science,15(2), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619867106

Beal, B. (2021). The nonmoral conditions of moral cognition. Philosophical Psychology, 34(8), 1097-1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2021.1942811

Beal, B., & Gogia, G. (2021). Cognition in moral space: A minimal model. Consciousness and Cognition, 92, 103134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2021.103134

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time (J. Stambaugh & D. Schmidt, Trans.). Albany: State University of New York Press. (Original work published 1927)

Much, N. C., & Shweder, R. A. (1978). Speaking of rules: The analysis of culture in breach. In W. Damon (Ed.), New Directions for Child Development: Moral Development (pp. 24–49). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shweder, R. A. (1992). Ghostbusters in anthropology. In R.G. D'Andrade and Claudia Strauss (Eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Reprinted in Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers nos. 69-70, 1989, pp. 100-108, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley).

Wittgenstein, L. (1997). Philosophical investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Oxford, England: Blackwell. (Original work published 1953)

Excellent post, Bree!

Although you’re not focusing on comparing your model to alternatives here, I still feel the need to start by expressing that this is a much-needed counter (or perhaps supplement – see below) to the values-centric models which have predominated moral psychology recently. My own view at this point is that models like Moral Foundations Theory may do a decent job at a descriptive/anthropological level (answering, “What categories of action tend to, or at least have the potential to be, moralized by humans?”) but that such models should never have made strong claims about being able to explain moral diversity (e.g., Do we really think individual differences in how much people value harm prevention in the abstract are going to be the best explanation for the tremendous moral diversity seen in, say, views on when and why it is acceptable to kill another person?) So whereas values-centric models like MFT may supplement and help clarify certain aspects of your model – namely, what sorts of actions might be counted as “behaving better/worse toward X”– I don’t think they get us much closer to explaining why people apply rules like “do no harm” with as much flexibility as they do in practice (where your model comes in!)

Two big questions I had after reading, though:

(1) The notion that moral judgments derive entirely from “is” beliefs strikes me as the strongest claim here and I wonder about certain aspects of this. With respect to “builders,” I agree that agency and existential closeness would count as descriptive “is” beliefs but isn’t there an “ought” contained within the notion of inherent value? It seems to me that a belief that “X is inherently valuable” is translatable to, “It would be better for X to exist [or be treated well] than to not exist [or be treated poorly]” – in other words, “X ought to exist” or “X ought to be treated well.” I had a similar thought about a potentially hidden “ought” premise in your screwdriver example, as well; following Belief #2, wouldn’t we need one additional premise along the lines of, “It would be better for me to complete my present task than not complete it” (i.e., “I ought to complete my present task”) to arrive at your conclusion?

(2) I really like the “builders/benders/attractors” taxonomy and am on board with the notion that the combination of these variables is likely to have far greater predictive validity for a wide range of moral judgments as compared to something like the MFQ (in other words, exactly what you found in the article with Rottman, which I hope gets published soon!) Something I wondered about, though, is how you conceptualize the relationship between these three different components and relatedly, where builder beliefs come from in the first place (and what would explain diversity in builder beliefs). For example, I think a lot of social science research supports the general notion that one’s ingroup/culture is determinative of many of their builder beliefs about to whom we owe moral consideration (e.g., as much as I might like to attribute my conviction that “slavery is wrong” to my own internal moral compass and rational faculties, this conviction is likely attributable in large part to the fact that this is what pretty much everyone around me has believed from the time I was born). Would this be an example of a builder belief being foundationally rooted in certain “attractor beliefs” (e.g., I ought to believe what others around me believe) and would your model allow for this sort of thing? I’m not sure that you explicitly say anything here that goes against this, but I wondered whether this would be consistent with your characterization of builder beliefs as having relatively stronger effects upon moral judgment than attractor beliefs (as opposed to the case above, where I'd argue that attractor beliefs have quite strong effects in that they are causally responsible for the builder beliefs in question). It’s possible all of this is just a misinterpretation of “attractors” but I was curious to hear your thoughts. Also just to be clear, I’m not saying attractors would be the only basis for builder beliefs and variability therein (e.g., I think other builder beliefs, such as “my offspring are inherently valuable and must be protected” could be explained fairly well by innate/evolved tendencies rather than the sort of cultural evolution in morality I’m describing above).

Excited to read your future posts!

This is a thoughtful breakdown of a process and I feel like I have a grasp of thanks to this article! I would find it worthwhile to do a small group session where we deconstruct some of our unconscious beliefs in this manner and see if there are some patterns that shake out. Though, I'm sure you've done this work as part of your research.

Regarding the following:

"I’ll be applying my research experience toward the area of business strategy consulting. If that seems like an odd left turn, that’s because it is."

I disagree, I think your knowledge of the human condition will be a very interesting and unique asset that distinguishes you from others in the field!